HONOLULU — Our hunt for aliens has a potentially fatal flaw — we're the ones searching for them.

That's

a problem because we're a unique species, and alien-seeking scientists

are an even stranger and more specialized bunch. As a result, their

all-too human assumptions may get in the way of their alien-listening

endeavors. To get around this, the

Breakthrough Listen project, a $100-million initiative scouring the cosmos for signals of otherworldly beings as part of the

Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), is asking anthropologists to help unmask some of these biases.

"It's

kind of a joke at Breakthrough Listen," Claire Webb, an anthropology

and history of science student at the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology, said here on Jan. 8 at the 235th meeting of the American

Astronomical Society (AAS) in Honolulu. "They tell me: 'We're studying

aliens, and you're studying us.'"

Since 2017, Webb has worked with Breakthrough Listen to examine how

SETI researchers think about aliens, produce knowledge, and perhaps

inadvertently place anthropocentric assumptions into their work.

She sometimes describes her efforts as "making the familiar strange."

For

instance, your life might seem perfectly ordinary — maybe involving

being hunched over at a desk and shuttling electrons around between

computers — until examined through an anthropological lens, which points

out that this is not exactly a universal state of affairs. At the

conference, Webb presented a poster looking at how Breakthrough Listen

scientists use

artificial intelligence (AI) to sift through large data sets and try to uncover potential

technosignatures, or indicators of technology or tool use by alien organisms.

"Researchers

who use AI tend to disavow human handicraft in the machines they

build," Webb told Live Science. "They attribute a lot of agency to those

machines. I find that somewhat problematic and at the worst untrue."

Any

AI is trained by human beings, who present it with the types of signals

they think an intelligent alien might produce. In doing so, they

predispose their algorithms to certain biases. It can be incredibly

difficult to recognize such thinking and overcome its limitations, Webb

said.

Most SETI research assumes some level of commensurability,

or the idea that beings on different worlds will understand the universe

in the same way and be able to communicate about it with one another,

Webb said. Much of this research, for example, presumes a type of

technological commensurability, in which aliens broadcast messages using

the same radio telescopes we have built, and that we will be able to

speak to them using a universal language of science and math.

But how universal is our language of science, and how inevitable is

our technological evolution? Do alien scientists gather in large

buildings and present their work to one another via slides and lectures

and posters? And what bearing do such

human rituals have on the types of scientific knowledge researchers produce?

It

was almost like trying to take the perspective of a creature on another

planet, who might wonder about humanity and our odd modern-day

practices. "If E.T. was looking at us, what would they see?" Webb

asked.

The assumptions and anxieties of alien-hunters can creep

in in other ways. Because of the vast distances involved in sending a

signal through space, many SETI researchers have imagined receiving a

message from an older technological society. As astronomer and science

popularizer Carl Sagan famously said in his 1980 book and television

series "Cosmos," that might mean E.T. has lived through a "

technological adolescence" and survived nuclear proliferation or an apocalyptic climate meltdown.

But

those statements are based on the specific anxieties of our era, namely

nuclear war and climate change, and we can't automatically assume that

the history of another species will unfold in the same way, Webb said.

Veteran

SETI scientist Jill Tarter has told Webb that, in some ways, we are

looking for a better version of ourselves, speculating that a message

from the heavens will include blueprints for a device that can provide

cheap energy and help alleviate poverty.

The ideal of progress is

embedded in such narratives, Webb said, first of scientific and

technological progress, but also an implicit assumption of moral

advancement. "It's the idea that, as your technology develops, so does

your sense of ethics and morality," she said. "And I think that's

something that can be contested."

Even our hunt for organisms like ourselves suggests "a yearning for connectivity, reflective to me of a kind of

postmodern loneliness and isolation in the universe," she said.

Webb

joked that SETI researchers don't always understand the point of her

anthropological and philosophical examinations. But, she said, they are

open to being challenged in their ideas and knowing that they are not

always seeing the whole picture.

"One thing Jill [Tarter] has

said many times is, 'We reserve the right to get smarter,'" she said.

"We are doing what we think makes sense now, but we might one day be

doing something totally different."

Ultimately, the point of this

work is to get SETI researchers to start "noticing human behavior in

ways that could push SETI to do novel kinds of searches," Webb said.

"Inhabiting other mindscapes is potentially a very powerful tool in

cultivating new ways to do science."

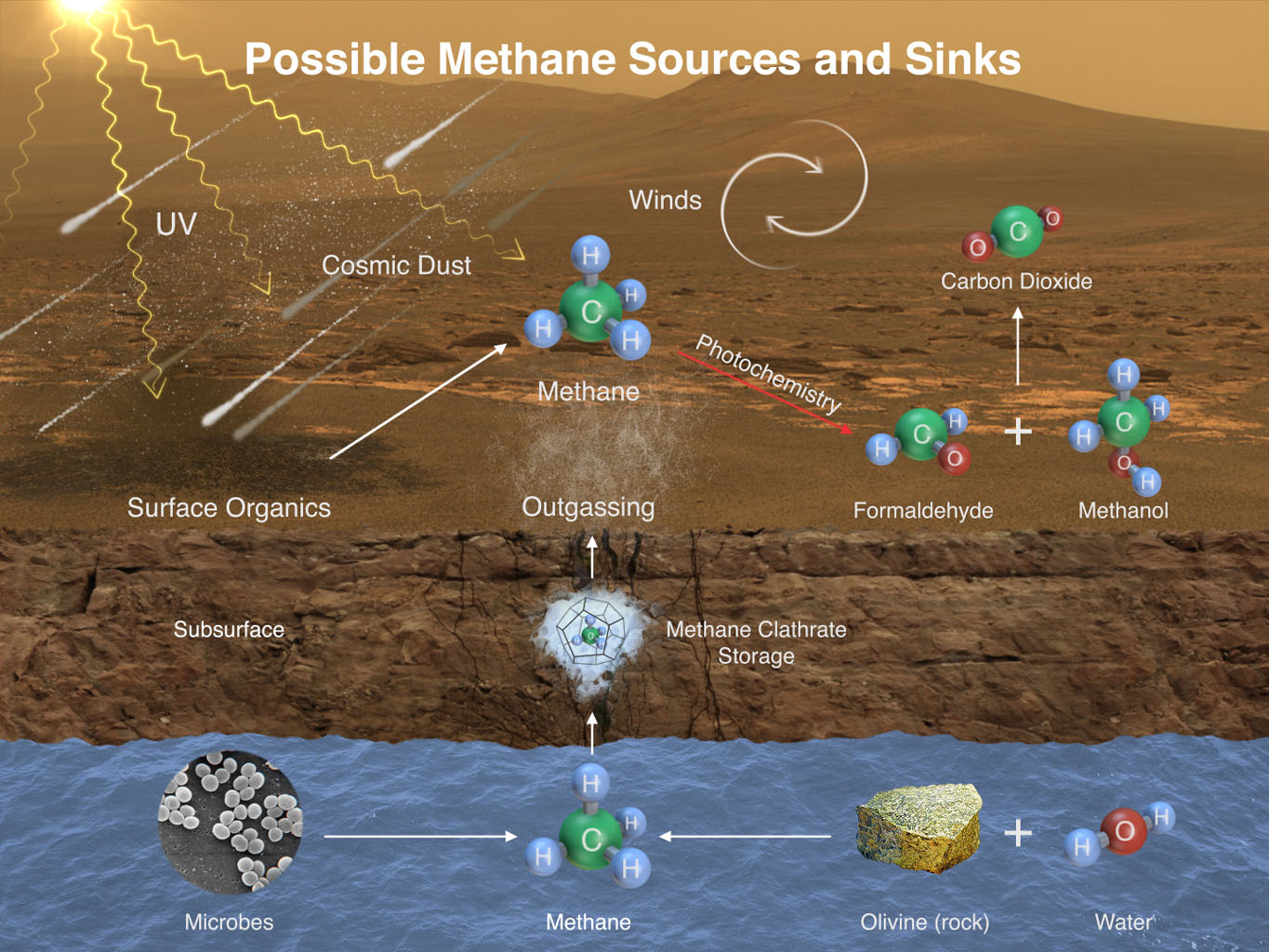

Perhaps beings on another

planet might use gravitational waves, or neutrinos, or even some other

unknown aspect of reality we have yet to come across to send messages

into the heavens.

Adam Mann

Source News

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-shropshirestar-mna.s3.amazonaws.com/public/SIPY7BEGJFFFDBJWENQK5RWGNU.jpg)

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-expressandstar-mna.s3.amazonaws.com/public/W4JT7GOFSZFLZODECUJLHZ6EWY.jpg)